|

Detail of a small-scale model of Venice, each building made by a different student in Sandro's second grade class

|

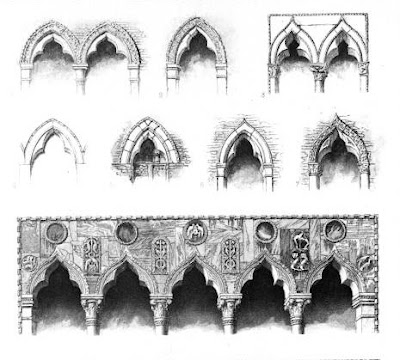

Last fall our son Sandro proudly returned home from school with drawings of different style Venetian windows he'd made during a

giretto (or "little walk") with his second grade class. This was a surprise for a couple of reasons: (1) because it hasn't been that long since he disliked having to do any kind of drawing in school and (2) because it also doesn't seem too long ago that, upon moving here, he proclaimed--repeatedly--how much he hated the way Venice looked. It was, he insisted each time we stepped outside our door that first November five years ago,

yucky,

ugly, and

too old! (

http://veneziablog.blogspot.it/2011/01/i-dont-like-venice.html)

Now he can't imagine ever leaving it. Though whether that's because the city's famed beauty has engraved itself upon his soul, as upon so many other souls over the centuries, is uncertain. For when asked by visitors what he likes best about living here, his answer is always the same: the fact that he can drive boats here, sometimes even large work boats (

mototopi). Whereas every other place we might live, on land where people travel in cars, he'd have to wait until he was sixteen to be able to tool around town.

|

| Sandro's first effort at cataloging some of Venice's windows |

In any case, he and his second grade classmates are now being asked to look at the world immediately around them in a methodical manner and to reproduce it on paper. This is something that some kids take to more readily than others, and the varying alacrity with which kids do this has made me realize how big a jump it actually is to go from the real, experienced three-dimensional world to a two-dimensional system of representing of it: whether that system involves a conventional repertoire of shapes (such as the triangle above a square that commonly represents a house in kids' drawings) or the alphabet.

I could imagine a fable in which the beauty of a city was such that its inhabitants refused to develop or use any system of two-dimensional representation, neither art nor writing, as traditionally it's said that both of those systems of representation are predicated upon, or inspired by, the absence of the thing represented. The prehistoric animal shapes on some cave wall were created to represent animals

not there, just as the first mythical artist, we are told, was inspired by the

absence of his or her beloved to paint the world's first rudimentary portrait. The residents of the city in my fable would refuse to denigrate the marvels of their beautiful home by representing them, by ever conceiving of them as anything other than fully, abundantly present all around them.

But that's a topic for another post.

|

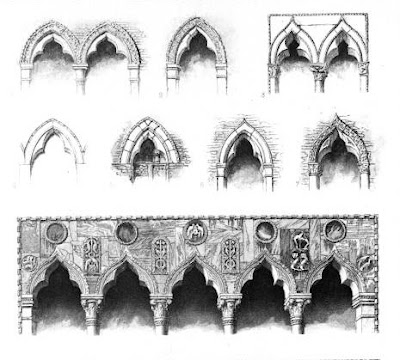

| A small sample of John Ruskin's catalog of Venetian arches |

Sandro's simple drawings of arches and the like in his school notebook actually made me think of John Ruskin's beautiful renderings of Venice's various styles of arch. All of Ruskin's painstaking depictions of Venice's architecture were--like the effort of the mythical first artist mentioned above--also inspired by absence and loss. But in Ruskin's case his beloved city of Venice--for which he evinced a passion notably lacking for his vivacious wife--was not yet gone but going,

and quickly, he believed

. Disintegrating like a sugar cube in hot tea, he said (resorting to an admirably English simile).

While Lord Byron, and visitors like him, had derived a gratifying melancholy from the city's deliquescence and seemingly inevitable collapse, Ruskin sounded an international alarm, warning the world of what it was about to lose.

And his alarm has continued to echo--quite softly at some periods, very loudly at others--pretty much ever since.

Though John Julius Norwich has reminded us that Venice, for all its serious current problems, is still in far better shape than it was at Ruskin's time, how many visitors to it can't help but think of it as a sinking city, a dying city? Even a dead city--or merely a museum? Or as the toothless old Queen of the Adriatic, bedridden and always a bit more crass and desperate and maybe even hopeless, but still working whatever she's got left for all it's worth? You know the images, the constant undercurrents...

I've actually met visitors to the city who were amazed to find out that things like elementary schools still exist at all in Venice!

Sandro's drawings of arches, however, turned all of this upside down for me. They weren't mournful or melancholy images of a world's end, souvenirs of something disappearing, or symbols of some imminent cultural or environmental collapse, but of a world's beginnings.

They are, quite literally, the starting points for his second grade class on their journey out into the broader world.

|

| Detail of a large poster made by Sandro's class |

For the teachers of his public school class--the same group of teachers that will remain with his class for each of its elementary school years (from grade 1 through 5)--have been following an educational course that began with the immediate and physical and experiential and is headed toward the more more far-reaching and abstract.

So that last year in first grade, for example, the class began to think about

and

represent how they live not just on paper with drawings, but by constructing a model of a house that was actually large enough for them to go inside. When it comes to minimizing the leap between actual experience and its conscious representation, that's about as small as you can, practically-speaking, make it. (Short of representing one's own house or school by building an exact scale replica of it.)

This year the students are well into reading and writing, and out in the world around them, sketching what they have seen from their earliest years but probably rarely ever tried to represent in a conscious way.

Of course what's nice about representing things in two-dimensions (or in small models) is that it not only gives you a way to record what you see, to re-present it as best you can, but also to manipulate and re-imagine those things in a way that's not so easy to do with the things themselves. The distance between the system of representation and the thing itself represented is not, in other words, only an indication of some loss or absence but of

possibility: it is the space of conceptualization, of thought, of imagination, and, potentially, of creation and change.

In Sandro's case it marks a third stage in his relationship with the city of Venice. His initial emphatic rejection of its alien otherness was followed by an even stronger and more complete immersion in it. For Venice, with its absence of cars, is a uniquely hospitable urban space for children, offering even the youngest of them the chance to run free as kings and queens of its

calli and

campi (see, for example,

http://veneziablog.blogspot.it/2012/03/wild-in-streets-or-calli.html).

Now, with his class, through writing and drawing, he's begun the process of learning of the city as not just given and lived in and immediate, but as something that can be regarded from a certain distance, as an object of thought. Learning about the city and its past becomes for them a model for learning about the broader world and a past beyond one's own personal past.

It's an amazing process to watch and participate in, this one of education, and immensely under-appreciated it seems to me in the two countries of which I'm a citizen, America and Italy, except as a means to a career, to money-making. It can, of course, be that--though not always, as more and more college graduates in both countries are discovering. But more essentially it is a process of awakening that's perhaps even more striking when it takes place in a city often said to be "dead," like Venice.

Moreover, there are people here who argue that this process of taking Venice

as a model from which to start thinking about the larger world (and, specifically, many of its most serious challenges, such as climate change) could prove beneficial to more than just local students. But that, too, is a topic for another post.